Monday, October 27, 2008

Influential Governments in the Agenda-Setting Process

In my previous blog, I discussed the large impact Canada had in implementing conflict diamonds onto the global agenda via their power on the UN Security Council in the late 1990s. On the Security Council, Canada was able to secure support from both the US and the UK. The Clinton Administration was slow to pick up the issue prior to 1999, but with mounting pressure the US was supportive in tightening the sanctions against UNITA. The US Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright, began addressing the issue. Tony Blair's government also began to show support for Canada's interest in addressing the issue. At the Miyazaki Initiatives for Conflict Prevention in 2000, the G8 focused their attention on the issue and formed a statement. They all expressed their support for the UN's effort in ending the illicit trade of diamonds. (Nossal, 260). The support of these powerful nations helped propel the issue onto the global agenda.

Monday, October 20, 2008

The UN’s Approach to Conflict Diamonds

According to the UN’s website the UN’s General Assembly, on December 1, 2001, adopted, unanimously, a resolution “on the role of diamonds in fuelling conflict, breaking the link between the illicit transaction of rough diamonds and armed conflict, as a contribution to prevention and settlement of conflicts (A/RES/55/56).”

The adoption of this resolution and the attention given to the issue by the UN is the result of several factors. Kim Richard Nossal discusses them in her article, “Smarter, Sharper, Stronger? UN Sanctions and Conflict Diamonds.” She explains how, in 1993, the UN Security Council unsuccessfully placed sanctions on União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola (UNITA)- the fighting rebel group in Angola who refused to recognize the results of the UN-supervised elections. These sanctions were largely unsuccessful, like many other UN sanctions of the 1990s, because of their “undifferentiated impact on all those who happened to live within a state targeted by sanctions” and also the weak capacity of the UN to enforce its legislation (250-251).

The late 1990s brought a new debate within the UN on the implementation of effective sanctions. Along with this debate came several other events that helped propel the issue of conflict diamonds onto the agenda. First, in January of 1999 Canada began its two year term on the Security Council and Robert Fowler (a Canadian) was placed on the chair of the Angola Sanctions Committee. (254). Secondly, conflict was increasing in Angola and there was a “renewed” interest in the media about the failure of UN sanctions. This was spurred in large part by the report released by Global Witness, A Rough Trade, which criticized the effectiveness of the UN sanctions in Angola. (256). Thirdly, “merely days after the release of the Global Witness report, UNITA shot down two UN planes.” (256). Canada took its seat on the Security Council the same day one of the planes went down. These events “galvanized” the council’s opinions on acting on the issue of Angola and the diamond trade. (255-256).

Nossal observed how Fowler was able “to pursue a multifaceted diplomatic strategy designed to address the leakage in the measures against UNITA and thus to pursue Canada’s broader UN agenda [reevaluating sanction policy].” (257). Fowler created a UN panel of experts to investigate the problem of conflict diamonds. The panel traveled to 30 countries, talked to members of the industry, heads of government, and NGOs. They presented their findings in a report in December of 2000.

Fowler’s approach reflects the unique Canadian approach to foreign policy. He greatly relied upon the work of NGOs to inform him of the issue. Fowler had established connections with Human Rights Watch and Global Witness. (258). Canadian government lent their support to these groups because they realize “the importance of publicity generated by such campaigns.” (259). The Canadian led Security Council, also, did not hesitate to use what Nossal refers to as the “naming and shaming” game. For the first time, these UN reports did not hesitate to blame certain states for their actions in ignoring and therefore abetting the problem. (261). For all these reasons discussed in this blog, the UN has become strong actor in the issue of conflict diamonds.

Reference:

Nossal, Kim Richard "Smarter, Sharper, Stronger? UN Sanctions and Conflict Diamonds." Cooper, Andrew Fenton, John English, and Ramesh Chandra Thakur. Enhancing Global Governance : Towards a New Diplomacy? Foundations of Peace. Tokyo ; New York: United Nations University Press, 2002.

Below is a list of sites that link you to the UN’s work on Conflict Diamonds:

http://www.un.org/peace/africa/Diamond.html

http://www.globalwitness.org/pages/en/the_united_nations_and_conflict_diamonds.html

http://www.globalpolicy.org/security/issues/diamond/unindex.htm

The adoption of this resolution and the attention given to the issue by the UN is the result of several factors. Kim Richard Nossal discusses them in her article, “Smarter, Sharper, Stronger? UN Sanctions and Conflict Diamonds.” She explains how, in 1993, the UN Security Council unsuccessfully placed sanctions on União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola (UNITA)- the fighting rebel group in Angola who refused to recognize the results of the UN-supervised elections. These sanctions were largely unsuccessful, like many other UN sanctions of the 1990s, because of their “undifferentiated impact on all those who happened to live within a state targeted by sanctions” and also the weak capacity of the UN to enforce its legislation (250-251).

The late 1990s brought a new debate within the UN on the implementation of effective sanctions. Along with this debate came several other events that helped propel the issue of conflict diamonds onto the agenda. First, in January of 1999 Canada began its two year term on the Security Council and Robert Fowler (a Canadian) was placed on the chair of the Angola Sanctions Committee. (254). Secondly, conflict was increasing in Angola and there was a “renewed” interest in the media about the failure of UN sanctions. This was spurred in large part by the report released by Global Witness, A Rough Trade, which criticized the effectiveness of the UN sanctions in Angola. (256). Thirdly, “merely days after the release of the Global Witness report, UNITA shot down two UN planes.” (256). Canada took its seat on the Security Council the same day one of the planes went down. These events “galvanized” the council’s opinions on acting on the issue of Angola and the diamond trade. (255-256).

Nossal observed how Fowler was able “to pursue a multifaceted diplomatic strategy designed to address the leakage in the measures against UNITA and thus to pursue Canada’s broader UN agenda [reevaluating sanction policy].” (257). Fowler created a UN panel of experts to investigate the problem of conflict diamonds. The panel traveled to 30 countries, talked to members of the industry, heads of government, and NGOs. They presented their findings in a report in December of 2000.

Fowler’s approach reflects the unique Canadian approach to foreign policy. He greatly relied upon the work of NGOs to inform him of the issue. Fowler had established connections with Human Rights Watch and Global Witness. (258). Canadian government lent their support to these groups because they realize “the importance of publicity generated by such campaigns.” (259). The Canadian led Security Council, also, did not hesitate to use what Nossal refers to as the “naming and shaming” game. For the first time, these UN reports did not hesitate to blame certain states for their actions in ignoring and therefore abetting the problem. (261). For all these reasons discussed in this blog, the UN has become strong actor in the issue of conflict diamonds.

Reference:

Nossal, Kim Richard "Smarter, Sharper, Stronger? UN Sanctions and Conflict Diamonds." Cooper, Andrew Fenton, John English, and Ramesh Chandra Thakur. Enhancing Global Governance : Towards a New Diplomacy? Foundations of Peace. Tokyo ; New York: United Nations University Press, 2002.

Below is a list of sites that link you to the UN’s work on Conflict Diamonds:

http://www.un.org/peace/africa/Diamond.html

http://www.globalwitness.org/pages/en/the_united_nations_and_conflict_diamonds.html

http://www.globalpolicy.org/security/issues/diamond/unindex.htm

Monday, October 6, 2008

The Media's Role in putting Conflict Diamonds on the Global Agenda

In the case of conflict diamonds, the media was the tool that a group of small NGOs used to propel the issue onto the global agenda. The media was one of the first targets of these NGOs, specifically newspapers. The coalition Fatal Attraction (discussed in the previous blog) sent editors of large newspapers fake diamond rings in jewelers’ boxes with information on how diamonds fueled wars in Africa (Grant and Taylor). Through my research, this campaign seems to have been effective in attracting the media’s attention- specifically the major Western newspapers.

It is first important to note how I conducted my research. By using the search engine LexisNexis, I was able to track the chronological order in which larger news sources began reporting on the issue of conflict diamonds. By using LexisNexis, I decided to focus my attention on the medium of newspapers and journals. I performed a search on “conflict diamonds” in the past 15 years. The results of my search seem to prove a relationship between the actions of Fatal Action and the issue adoption of major news sources.

Global Witness released their first report on the issue, “A Rough Trade: The Role of Companies and Governments in the Angolan Conflict,” in 1998. In October of 1999, Fatal Transaction began its campaign. (Grant and Taylor). Between the release of the initial report and the start of the Campaign, only a handful of articles were written about the issue. The majority of these articles were written for Africa News, and some of them were written by Global Witness. In The New York Times on August 8, 1999 a short editorial was published: “The Business of War in Africa,” but it wasn’t until October of 1999 that I observed a proliferation of major newspapers reporting on this issue; such as The Times (London), Sydney Morning Herald, The Washington Post, Newsweek, The Economist and the UN began issuing reports to Africa News. I think the proliferation of attention this issue received from the media can be attributed to Fatal Attraction’s campaign, and not as just a mere coincidence.

After the issue grabbed the media’s attention, the UN signed the resolution on conflict diamonds on December 1, 2000. My research showed that between October 1999 and December 2000, 167 articles had been written about conflict diamonds. I think it is safe to state that the UN passed the resolution in part due to the pressure the global media.

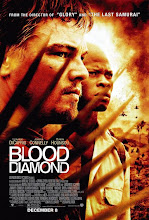

The major newspapers and journals have continued to follow the issue through the establishment of the Kimberely Process, and the release of the movie Blood Diamond. Below is the number of hits my search received from the major news sources on the issue of “conflict diamonds” in the past 15 years:

The New York Times: 27

The Times (London): 36

The Washington Post: 19

Newsweek: 5

The Economist: 3

Overall for Magazines, Journals, and Newspapers: 568

The work of Fatal Attraction and other NGOs properly attracted the attention of the written media. Without the attention and cooperation of these major media outlets, the issue of conflict diamonds may have never made it to the global agenda.

References:

Grant, Andrew, and Ian Taylor. "Global Governance and Conflict Diamonds: The Kimberley Process and the Quest for Clean Gems." The Round Table 93 (2004): 385-401.

It is first important to note how I conducted my research. By using the search engine LexisNexis, I was able to track the chronological order in which larger news sources began reporting on the issue of conflict diamonds. By using LexisNexis, I decided to focus my attention on the medium of newspapers and journals. I performed a search on “conflict diamonds” in the past 15 years. The results of my search seem to prove a relationship between the actions of Fatal Action and the issue adoption of major news sources.

Global Witness released their first report on the issue, “A Rough Trade: The Role of Companies and Governments in the Angolan Conflict,” in 1998. In October of 1999, Fatal Transaction began its campaign. (Grant and Taylor). Between the release of the initial report and the start of the Campaign, only a handful of articles were written about the issue. The majority of these articles were written for Africa News, and some of them were written by Global Witness. In The New York Times on August 8, 1999 a short editorial was published: “The Business of War in Africa,” but it wasn’t until October of 1999 that I observed a proliferation of major newspapers reporting on this issue; such as The Times (London), Sydney Morning Herald, The Washington Post, Newsweek, The Economist and the UN began issuing reports to Africa News. I think the proliferation of attention this issue received from the media can be attributed to Fatal Attraction’s campaign, and not as just a mere coincidence.

After the issue grabbed the media’s attention, the UN signed the resolution on conflict diamonds on December 1, 2000. My research showed that between October 1999 and December 2000, 167 articles had been written about conflict diamonds. I think it is safe to state that the UN passed the resolution in part due to the pressure the global media.

The major newspapers and journals have continued to follow the issue through the establishment of the Kimberely Process, and the release of the movie Blood Diamond. Below is the number of hits my search received from the major news sources on the issue of “conflict diamonds” in the past 15 years:

The New York Times: 27

The Times (London): 36

The Washington Post: 19

Newsweek: 5

The Economist: 3

Overall for Magazines, Journals, and Newspapers: 568

The work of Fatal Attraction and other NGOs properly attracted the attention of the written media. Without the attention and cooperation of these major media outlets, the issue of conflict diamonds may have never made it to the global agenda.

References:

Grant, Andrew, and Ian Taylor. "Global Governance and Conflict Diamonds: The Kimberley Process and the Quest for Clean Gems." The Round Table 93 (2004): 385-401.

Monday, September 29, 2008

NGOs: The Central Force for Change on the Issue of Conflict Diamonds

In exposing the issue of conflict diamonds, NGO’s have been at the very center of the agenda-setting process and continue to play an important role in monitoring the issue. The two central NGO’s who carried out the movement were Global Witness and Partnership Africa Canada (PAC). Their importance is best exemplified by their 2003 Nobel Peace Prize nomination in 2003. The nomination cites the central role of Global Witness in the movement by quoting Matthew Hart in his book, Diamond: A Journey to the Heart of an Obsession:

“The diamond wars were the secret of the diamond trade until, quite suddenly, they were not. It seemed to happen in an instant, as if a curtain had been ripped aside and there was the diamond business, spattered with blood, sorting through the goods. Its accuser was a little-known group called Global Witness.”

The nomination also cites the initial report put out by Global Witness followed by another report put out by PAC were crucial in exposing the diamond industry to the world. Other written works and activism of the two organizations have contributed to an international awareness of conflict diamonds.

An article by Grant and Taylor describes Global Witness’s first report, “A Rough Trade: The Role of Companies and Governments in the Angolan Conflict,” as being “paramount in exposing…the role of diamonds in funding the Angolan civil war.” (390). After the 1998 Global Witness report, their convictions were strengthened in 2000 by PAC’s report: “The Heart of the Matter: Sierra Leone, Diamonds and Human Security.” These two important reports, followed by some others, have provided substantive knowledge and evidence that backs their claims for change.

Global Witness and PAC partnered together and disseminated their message to a diversified audience. Grant and Taylor refer to their method as “multi-track” diplomacy, which works by building “mixed-actor networks.” (386), but before establishing these networks, they had to frame their issue. Philippe Le Billion exemplifies the framing of conflict diamonds as a new trend in framing transnational issues around consumer rights, which is defined as being “individuals bearing indirect responsibility for the perpetuation of acts of extreme violence against civilians through their consumption practices.” (779). Le Billion describes consumer politics as a new “potent force of change.” (779). This framing became more affective after the events of September 11, when al Qaeda was protecting its money by “sinking its money into gems.” (Grant and Taylor, 388). As soon as terrorism was linked to the diamond industry, the US and other states became interested in bringing the issue to the global agenda.

The successful framing of their issue led to a successful building in several coalitions of NGOs in Europe and the US. In October 1999, a coalition of four European NGOs, entitled “Fatal Transactions” began to send information to media outlets. They sent pamphlets in “jewelers’ boxes” with “cut-glass diamond rings” to newspaper editors (Grant and Taylor, 390). The campaign also came up with several powerful images and phrases, such as “amputation is forever.” In the US, Amnesty International became involved and started disseminating lists of jewelers who sold conflict diamonds. (Grant and Taylor, 391).

On Valentines Day in 2001, a group of 100 NGOs in the United States signed a public letter to the diamond industry urging them to not “let diamonds go the way of fur.” (Grant and Taylor, 391). “The Campaign to Eliminate Conflict Diamonds” was built around the concept of love and romance that the diamond trade markets. NGOs tried to encourage the diamond industry to address the issue so that it did not suffer the consequences of inaction, which could potentially lead to a boycott. (Grant and Taylor, 391). The diamond industry had no choice but to act when states and NGOs began to call for more oversight.

A number of South African countries came together in Kimberley, South Africa (after the passing of the UN Resolution on Conflict Diamonds in 2000) to begin to formulate the Kimberley Process. Global Witness and PAC played integral roles in the process, by proposing plans of action, maintaining pressure and a sense of urgency. (Grant and Taylor, 392). The NGOs success on this issue is largely attributed to their ability to negotiate with the diamond industry, to avoid generalizations, and to understand the complexity of the situation. This is best described in the letter for their Nobel Peace Prize nomination:

“They have succeeded in part because they have avoided polarizing campaign tactics that could have alienated the diamond industry and key governments, whose support is critical to a solution. They understood that, despite the shocking difference between the advertised image of diamonds and the often harsh reality of the trade, a boycott could result in a backlash against a product whose legitimate trade is the backbone of many economies.”

Global Witness, PAC, and Amnesty International are still very involved in overseeing the implementation of The Kimberley Process by offering reports of their findings. They also try to maintain pressure on states and the diamond industry to comply with the international established norm. The NGOs involved in this issue have been central to putting conflict diamonds on the global agenda by framing the issue as a consumer right’s issue and by “multi-tracking” the issue through various actors.

“The diamond wars were the secret of the diamond trade until, quite suddenly, they were not. It seemed to happen in an instant, as if a curtain had been ripped aside and there was the diamond business, spattered with blood, sorting through the goods. Its accuser was a little-known group called Global Witness.”

The nomination also cites the initial report put out by Global Witness followed by another report put out by PAC were crucial in exposing the diamond industry to the world. Other written works and activism of the two organizations have contributed to an international awareness of conflict diamonds.

An article by Grant and Taylor describes Global Witness’s first report, “A Rough Trade: The Role of Companies and Governments in the Angolan Conflict,” as being “paramount in exposing…the role of diamonds in funding the Angolan civil war.” (390). After the 1998 Global Witness report, their convictions were strengthened in 2000 by PAC’s report: “The Heart of the Matter: Sierra Leone, Diamonds and Human Security.” These two important reports, followed by some others, have provided substantive knowledge and evidence that backs their claims for change.

Global Witness and PAC partnered together and disseminated their message to a diversified audience. Grant and Taylor refer to their method as “multi-track” diplomacy, which works by building “mixed-actor networks.” (386), but before establishing these networks, they had to frame their issue. Philippe Le Billion exemplifies the framing of conflict diamonds as a new trend in framing transnational issues around consumer rights, which is defined as being “individuals bearing indirect responsibility for the perpetuation of acts of extreme violence against civilians through their consumption practices.” (779). Le Billion describes consumer politics as a new “potent force of change.” (779). This framing became more affective after the events of September 11, when al Qaeda was protecting its money by “sinking its money into gems.” (Grant and Taylor, 388). As soon as terrorism was linked to the diamond industry, the US and other states became interested in bringing the issue to the global agenda.

The successful framing of their issue led to a successful building in several coalitions of NGOs in Europe and the US. In October 1999, a coalition of four European NGOs, entitled “Fatal Transactions” began to send information to media outlets. They sent pamphlets in “jewelers’ boxes” with “cut-glass diamond rings” to newspaper editors (Grant and Taylor, 390). The campaign also came up with several powerful images and phrases, such as “amputation is forever.” In the US, Amnesty International became involved and started disseminating lists of jewelers who sold conflict diamonds. (Grant and Taylor, 391).

On Valentines Day in 2001, a group of 100 NGOs in the United States signed a public letter to the diamond industry urging them to not “let diamonds go the way of fur.” (Grant and Taylor, 391). “The Campaign to Eliminate Conflict Diamonds” was built around the concept of love and romance that the diamond trade markets. NGOs tried to encourage the diamond industry to address the issue so that it did not suffer the consequences of inaction, which could potentially lead to a boycott. (Grant and Taylor, 391). The diamond industry had no choice but to act when states and NGOs began to call for more oversight.

A number of South African countries came together in Kimberley, South Africa (after the passing of the UN Resolution on Conflict Diamonds in 2000) to begin to formulate the Kimberley Process. Global Witness and PAC played integral roles in the process, by proposing plans of action, maintaining pressure and a sense of urgency. (Grant and Taylor, 392). The NGOs success on this issue is largely attributed to their ability to negotiate with the diamond industry, to avoid generalizations, and to understand the complexity of the situation. This is best described in the letter for their Nobel Peace Prize nomination:

“They have succeeded in part because they have avoided polarizing campaign tactics that could have alienated the diamond industry and key governments, whose support is critical to a solution. They understood that, despite the shocking difference between the advertised image of diamonds and the often harsh reality of the trade, a boycott could result in a backlash against a product whose legitimate trade is the backbone of many economies.”

Global Witness, PAC, and Amnesty International are still very involved in overseeing the implementation of The Kimberley Process by offering reports of their findings. They also try to maintain pressure on states and the diamond industry to comply with the international established norm. The NGOs involved in this issue have been central to putting conflict diamonds on the global agenda by framing the issue as a consumer right’s issue and by “multi-tracking” the issue through various actors.

Monday, September 22, 2008

Celebrities: Helpful or Harmful?

"In America its bling bling but out here its bling bang!"

-Blood Diamond (the movie)

To study how much of an impact celebrities have had on making substantive changes on the issue of Conflict Diamonds, I think it is important to consider the timeline of events. In 2000, the UN passed the resolution on Conflict Diamonds six years before Hollywood entered the dialogue with the release of the film Blood Diamond. If one is to assume that a UN Resolution is the measure of whether an issue has made it to the global agenda then the issue of Conflict Diamonds made it on the agenda well before celebrities advocated on the behalf of its victims. The role celebrities and Hollywood play on the issue of Conflict Diamonds was to bring the issue to a larger audience, and to remember the victims of the conflicts. Celebrities also have sparked dialogue- between each other, with states, and with the diamond industry. The rest of this blog will present the debates that emerged around the issue after the 2000 UN resolution.

On December 15, 2006, Warner Brothers released the film Blood Diamonds directed by Edward Zwick. The film takes place during the Sierra Leone Civil War of 1999. It tells the story of a Western journalist, Rhodesian diamond smuggler, and an African fisherman in search of his son, who was kidnapped by the rebel forces. The film exposes the diamond industry’s exploitation of the African mineral. The film also caught attention because Leonardo DiCaprio played the main character. Amnesty International and Global Witness also sponsored this film.

In my research, I have found that Leonardo DiCaprio was not as outspoken about the issue of Conflict Diamonds as I had thought. In interviews he steered away from passing judgment on the industry today, this is exemplified in one of his responses to an Entertainment Weekly interview:

The reporter asked: “Did making this movie change your opinion about diamonds?”

He responded:”[Deep breath] Well, without getting into the whole political aspect, because I think the movie should speak for that, to me diamonds represent any sort of natural resource that we get from foreign countries and how that affects the economy and the politics and the conditions of those people.”

Also, in tracking DiCaprio’s involvement with charities on http://www.looktothestars.org/, I found he is not affiliated with any group with a clear connection to the issue of Conflict Diamonds.

Other celebrities have been more outspoken about this issue than DiCaprio has been. According the Los Angeles Times, the director, Edward Zwick, faced a lot of pressure from the diamond industry to make clear in the publicity of the film that this was no longer a problem because The Kimberely Process has been 99% effective. Zwick refused. The industry then “began its multimillion-dollar campaign to ‘educate consumers’ about the Kimberley Process.

After the movie, Zwick was asked to speak at the 2007 International Diamond Conference in New York. His speech called the diamond industry to take responsibility of the people they exploit.

The reaction that the film received was both surprising and predictable. The Diamond Industry obviously lobbied against exposing its inconsistencies with The Kimberely Process, but more surprisingly was that notably celebrities spoke in favor of the diamond industries attempts to help Africans. Russell Simmons, a famous rapper, started an organization called Diamond Empowerment Fund or D.E.F. Before the movie came out, Simmons went on a fact finding mission (sponsored by the diamond industry) to see how the diamond industry is helping Africans out of poverty. Zwick criticized Simmons, but in an article on africaResource Simmons defends his position:

"But to suggest I'm a sellout is wrong. I'm not here to defend the past of these companies. I'm here to talk about the current reality. Diamonds pay for education and medical treatment in Africa."

Simmons organization is also the only charity that comes up on http://www.looktothestars.org/. Celebrities who are related to this charity are Beyonce, Nelson Mandela, and Naomi Campbell. It was also recently reported that Gisele Bundchen will be donating “a personal collection of dazzling bling in a special auction at Christie’s New York next month.”

In addition to Simmons activism on the issue, other rappers have decided to be vocal on the issue. Nas released a video for the movie, Blood Diamonds. Kanye West also released a song entitled “Diamonds from Sierra Leone.”

Kanye was also featured in a VH1 special on Conflict Diamonds that came out around the same time of the movie. Bling: A Planet Rock, discusses the irony of how diamonds empower the urban black rappers that came from little, while at the same time disenfranchising black people in Africa.

The 2006 movie, Blood Diamond, expanded the debate on Conflict Diamonds, whether it brought significant change still cannot be determined. My research could not find any conclusive evidence that substantial research had been done on the movie’s impact on the issue.

Monday, September 15, 2008

Placing Conflict Diamonds on the Issue Continuum

In 1998, the NGO, Global Witness, championed the issue of conflict diamonds to the global stage. Global Witness sought to “to break the links between the exploitation of natural resources in conflict and corruption” that they observed in several African conflicts. They also acknowledged that the results of their “investigations” and their “powerful lobbying skills have been not only a catalyst, but a main driver behind most of the major international mechanisms and initiatives that have been established to address these issues.”

Global Witness, as they explain on their website, started out as a very small NGO but grew into an enormous operation:

“Established in 1993 by the three founding directors working from the front rooms of their homes, Global Witness now numbers over forty staff divided between its offices in London and Washington DC, and has built a truly impressive track record of success.”

Their beginnings resemble those of CIVIC, therefore CIVIC will benefit greatly from the presentation of Global Witness’s rise to fame.

Global Witness’s self-proclamation of their successes is confirmed by the fact that major international players adopted conflict diamonds as an issue on the global stage. Under their broad issue of exploitation of resources in conflict zones, they were able to select a specific “issue characterization” that would resonate to other NGOs and other actors. (Keck and Sikkink) The bodily harm and suffering of the victims in conflict diamond mines presents a definitive issue, in which others would be able to connect. CIVIC should consider narrowing their issue to accomplish their broader goal.

Large “gatekeeper” NGOs adopted the conflict diamonds issue as an important cause, the most important being Amnesty International (AI). On their website, AI also acknowledges that they have been extremely instrumental in the global recognition of this issue:

“1998 Global Witness began a campaign to expose the role of diamonds in funding conflicts. As the largest grassroots human rights organization in the world, Amnesty International has been instrumental in educating the public about the problem, and pressing governments and industry to take action.”

AI adopted Global Witness’s cause and helped expand a large network of other NGOs to commit their support to the cause. The inclusion of many different NGOs attributes to the great amount of saliency this issue holds.

After many NGOs adopted the issue, other actors recognized the issue- most importantly the UN and governments. As previously blogged, the UN adopted a resolution in 2000 in regards to the funding of wars with conflict diamonds. Since then The Kimberely Process has been created to implement change. Although it may seem that this issue has reached a level of international norms, Global Witness and others recognize the discrepancies between the policies in place versus the action/change that has occurred:

“Despite the great strides made in the first decade of Global Witness' existence, the struggle to ensure that natural resource exploitation is equitable and sustainable is still in its early stages.”

The Kimberely Process is not working as efficiently as it should be and there is not enough oversight. This is to blame on the diamond industry, the IGOs and governments.

Recognizing these discrepancies, I would place the issue of conflict diamonds in the advocacy/campaign stage because “Practices do not simply echo norms- they make them real.” (Keck and Sikkink, 35). Without properly overseeing the institutions that supposedly regulate the problem, the issue is not yet a global norm because it is not properly implemented.

Global Witness, as they explain on their website, started out as a very small NGO but grew into an enormous operation:

“Established in 1993 by the three founding directors working from the front rooms of their homes, Global Witness now numbers over forty staff divided between its offices in London and Washington DC, and has built a truly impressive track record of success.”

Their beginnings resemble those of CIVIC, therefore CIVIC will benefit greatly from the presentation of Global Witness’s rise to fame.

Global Witness’s self-proclamation of their successes is confirmed by the fact that major international players adopted conflict diamonds as an issue on the global stage. Under their broad issue of exploitation of resources in conflict zones, they were able to select a specific “issue characterization” that would resonate to other NGOs and other actors. (Keck and Sikkink) The bodily harm and suffering of the victims in conflict diamond mines presents a definitive issue, in which others would be able to connect. CIVIC should consider narrowing their issue to accomplish their broader goal.

Large “gatekeeper” NGOs adopted the conflict diamonds issue as an important cause, the most important being Amnesty International (AI). On their website, AI also acknowledges that they have been extremely instrumental in the global recognition of this issue:

“1998 Global Witness began a campaign to expose the role of diamonds in funding conflicts. As the largest grassroots human rights organization in the world, Amnesty International has been instrumental in educating the public about the problem, and pressing governments and industry to take action.”

AI adopted Global Witness’s cause and helped expand a large network of other NGOs to commit their support to the cause. The inclusion of many different NGOs attributes to the great amount of saliency this issue holds.

After many NGOs adopted the issue, other actors recognized the issue- most importantly the UN and governments. As previously blogged, the UN adopted a resolution in 2000 in regards to the funding of wars with conflict diamonds. Since then The Kimberely Process has been created to implement change. Although it may seem that this issue has reached a level of international norms, Global Witness and others recognize the discrepancies between the policies in place versus the action/change that has occurred:

“Despite the great strides made in the first decade of Global Witness' existence, the struggle to ensure that natural resource exploitation is equitable and sustainable is still in its early stages.”

The Kimberely Process is not working as efficiently as it should be and there is not enough oversight. This is to blame on the diamond industry, the IGOs and governments.

Recognizing these discrepancies, I would place the issue of conflict diamonds in the advocacy/campaign stage because “Practices do not simply echo norms- they make them real.” (Keck and Sikkink, 35). Without properly overseeing the institutions that supposedly regulate the problem, the issue is not yet a global norm because it is not properly implemented.

Monday, September 8, 2008

Conflict Diamonds: Introduction

Conflict diamonds or “blood diamonds” were defined by the UN in December of 2000 as: "...diamonds that originate from areas controlled by forces or factions opposed to legitimate and internationally recognized governments, and are used to fund military action in opposition to those governments, or in contravention of the decisions of the Security Council."(UN).

Conflict diamonds have been used by rebel groups to fuel brutal wars in Africa, more specifically the countries of Angola, Sierra Leone, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the Cote d’Ivoire. Rebels sell these diamonds to international diamond dealers to purchase large quantities of small arms. According to Amnesty International: “These conflicts have resulted in over 4 million deaths and the displacement of mill ions of people” in Africa.” (AIGW Fact sheet).

Not only do the diamonds fund destructive wars of the regions, but the actual mining process itself is detrimental to the miners’ well-being and keeps them below poverty lines. According to Amnesty International: “hundreds of thousands of men and children work in dirty, dangerous, and difficult conditions digging for diamonds, and they often earn less than a dollar a day. This is artisanal mining, carried out with simple picks, shovels and sieves.” (AI- The Truth about Diamonds).

As the international community became aware of the issue of conflict diamonds, the international diamond industry created the World Diamond Congress in July of 2000. The diamond industry along with NGOs, IGOs , and governments negotiated an international certification scheme “that that regulates trade in rough diamonds. It aims to prevent the flow of conflict diamonds, while helping to protect legitimate trade in rough diamonds.” This certification scheme is also known as The Kimberely Process. (The Kimberely Process).

Even though the World Diamond Process is claiming that The Kimberly Process is 99% effective (Diamond Facts), Amnesty International has found proof that this fact is false and claims: “The Kimberley Process is increasingly being hailed as a success and the problem of blood diamonds is perceived to be solved by some. This is leading to complacency and a lack of political will to improve the scheme.” (AI: Kimberely Process).

In the coming weeks this blog will explore the issue of conflict diamonds even further, and will trace its emergence as a major human security issue onto the global agenda.

Conflict diamonds have been used by rebel groups to fuel brutal wars in Africa, more specifically the countries of Angola, Sierra Leone, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the Cote d’Ivoire. Rebels sell these diamonds to international diamond dealers to purchase large quantities of small arms. According to Amnesty International: “These conflicts have resulted in over 4 million deaths and the displacement of mill ions of people” in Africa.” (AIGW Fact sheet).

Not only do the diamonds fund destructive wars of the regions, but the actual mining process itself is detrimental to the miners’ well-being and keeps them below poverty lines. According to Amnesty International: “hundreds of thousands of men and children work in dirty, dangerous, and difficult conditions digging for diamonds, and they often earn less than a dollar a day. This is artisanal mining, carried out with simple picks, shovels and sieves.” (AI- The Truth about Diamonds).

As the international community became aware of the issue of conflict diamonds, the international diamond industry created the World Diamond Congress in July of 2000. The diamond industry along with NGOs, IGOs , and governments negotiated an international certification scheme “that that regulates trade in rough diamonds. It aims to prevent the flow of conflict diamonds, while helping to protect legitimate trade in rough diamonds.” This certification scheme is also known as The Kimberely Process. (The Kimberely Process).

Even though the World Diamond Process is claiming that The Kimberly Process is 99% effective (Diamond Facts), Amnesty International has found proof that this fact is false and claims: “The Kimberley Process is increasingly being hailed as a success and the problem of blood diamonds is perceived to be solved by some. This is leading to complacency and a lack of political will to improve the scheme.” (AI: Kimberely Process).

In the coming weeks this blog will explore the issue of conflict diamonds even further, and will trace its emergence as a major human security issue onto the global agenda.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)