Monday, October 27, 2008

Influential Governments in the Agenda-Setting Process

In my previous blog, I discussed the large impact Canada had in implementing conflict diamonds onto the global agenda via their power on the UN Security Council in the late 1990s. On the Security Council, Canada was able to secure support from both the US and the UK. The Clinton Administration was slow to pick up the issue prior to 1999, but with mounting pressure the US was supportive in tightening the sanctions against UNITA. The US Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright, began addressing the issue. Tony Blair's government also began to show support for Canada's interest in addressing the issue. At the Miyazaki Initiatives for Conflict Prevention in 2000, the G8 focused their attention on the issue and formed a statement. They all expressed their support for the UN's effort in ending the illicit trade of diamonds. (Nossal, 260). The support of these powerful nations helped propel the issue onto the global agenda.

Monday, October 20, 2008

The UN’s Approach to Conflict Diamonds

According to the UN’s website the UN’s General Assembly, on December 1, 2001, adopted, unanimously, a resolution “on the role of diamonds in fuelling conflict, breaking the link between the illicit transaction of rough diamonds and armed conflict, as a contribution to prevention and settlement of conflicts (A/RES/55/56).”

The adoption of this resolution and the attention given to the issue by the UN is the result of several factors. Kim Richard Nossal discusses them in her article, “Smarter, Sharper, Stronger? UN Sanctions and Conflict Diamonds.” She explains how, in 1993, the UN Security Council unsuccessfully placed sanctions on União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola (UNITA)- the fighting rebel group in Angola who refused to recognize the results of the UN-supervised elections. These sanctions were largely unsuccessful, like many other UN sanctions of the 1990s, because of their “undifferentiated impact on all those who happened to live within a state targeted by sanctions” and also the weak capacity of the UN to enforce its legislation (250-251).

The late 1990s brought a new debate within the UN on the implementation of effective sanctions. Along with this debate came several other events that helped propel the issue of conflict diamonds onto the agenda. First, in January of 1999 Canada began its two year term on the Security Council and Robert Fowler (a Canadian) was placed on the chair of the Angola Sanctions Committee. (254). Secondly, conflict was increasing in Angola and there was a “renewed” interest in the media about the failure of UN sanctions. This was spurred in large part by the report released by Global Witness, A Rough Trade, which criticized the effectiveness of the UN sanctions in Angola. (256). Thirdly, “merely days after the release of the Global Witness report, UNITA shot down two UN planes.” (256). Canada took its seat on the Security Council the same day one of the planes went down. These events “galvanized” the council’s opinions on acting on the issue of Angola and the diamond trade. (255-256).

Nossal observed how Fowler was able “to pursue a multifaceted diplomatic strategy designed to address the leakage in the measures against UNITA and thus to pursue Canada’s broader UN agenda [reevaluating sanction policy].” (257). Fowler created a UN panel of experts to investigate the problem of conflict diamonds. The panel traveled to 30 countries, talked to members of the industry, heads of government, and NGOs. They presented their findings in a report in December of 2000.

Fowler’s approach reflects the unique Canadian approach to foreign policy. He greatly relied upon the work of NGOs to inform him of the issue. Fowler had established connections with Human Rights Watch and Global Witness. (258). Canadian government lent their support to these groups because they realize “the importance of publicity generated by such campaigns.” (259). The Canadian led Security Council, also, did not hesitate to use what Nossal refers to as the “naming and shaming” game. For the first time, these UN reports did not hesitate to blame certain states for their actions in ignoring and therefore abetting the problem. (261). For all these reasons discussed in this blog, the UN has become strong actor in the issue of conflict diamonds.

Reference:

Nossal, Kim Richard "Smarter, Sharper, Stronger? UN Sanctions and Conflict Diamonds." Cooper, Andrew Fenton, John English, and Ramesh Chandra Thakur. Enhancing Global Governance : Towards a New Diplomacy? Foundations of Peace. Tokyo ; New York: United Nations University Press, 2002.

Below is a list of sites that link you to the UN’s work on Conflict Diamonds:

http://www.un.org/peace/africa/Diamond.html

http://www.globalwitness.org/pages/en/the_united_nations_and_conflict_diamonds.html

http://www.globalpolicy.org/security/issues/diamond/unindex.htm

The adoption of this resolution and the attention given to the issue by the UN is the result of several factors. Kim Richard Nossal discusses them in her article, “Smarter, Sharper, Stronger? UN Sanctions and Conflict Diamonds.” She explains how, in 1993, the UN Security Council unsuccessfully placed sanctions on União Nacional para a Independência Total de Angola (UNITA)- the fighting rebel group in Angola who refused to recognize the results of the UN-supervised elections. These sanctions were largely unsuccessful, like many other UN sanctions of the 1990s, because of their “undifferentiated impact on all those who happened to live within a state targeted by sanctions” and also the weak capacity of the UN to enforce its legislation (250-251).

The late 1990s brought a new debate within the UN on the implementation of effective sanctions. Along with this debate came several other events that helped propel the issue of conflict diamonds onto the agenda. First, in January of 1999 Canada began its two year term on the Security Council and Robert Fowler (a Canadian) was placed on the chair of the Angola Sanctions Committee. (254). Secondly, conflict was increasing in Angola and there was a “renewed” interest in the media about the failure of UN sanctions. This was spurred in large part by the report released by Global Witness, A Rough Trade, which criticized the effectiveness of the UN sanctions in Angola. (256). Thirdly, “merely days after the release of the Global Witness report, UNITA shot down two UN planes.” (256). Canada took its seat on the Security Council the same day one of the planes went down. These events “galvanized” the council’s opinions on acting on the issue of Angola and the diamond trade. (255-256).

Nossal observed how Fowler was able “to pursue a multifaceted diplomatic strategy designed to address the leakage in the measures against UNITA and thus to pursue Canada’s broader UN agenda [reevaluating sanction policy].” (257). Fowler created a UN panel of experts to investigate the problem of conflict diamonds. The panel traveled to 30 countries, talked to members of the industry, heads of government, and NGOs. They presented their findings in a report in December of 2000.

Fowler’s approach reflects the unique Canadian approach to foreign policy. He greatly relied upon the work of NGOs to inform him of the issue. Fowler had established connections with Human Rights Watch and Global Witness. (258). Canadian government lent their support to these groups because they realize “the importance of publicity generated by such campaigns.” (259). The Canadian led Security Council, also, did not hesitate to use what Nossal refers to as the “naming and shaming” game. For the first time, these UN reports did not hesitate to blame certain states for their actions in ignoring and therefore abetting the problem. (261). For all these reasons discussed in this blog, the UN has become strong actor in the issue of conflict diamonds.

Reference:

Nossal, Kim Richard "Smarter, Sharper, Stronger? UN Sanctions and Conflict Diamonds." Cooper, Andrew Fenton, John English, and Ramesh Chandra Thakur. Enhancing Global Governance : Towards a New Diplomacy? Foundations of Peace. Tokyo ; New York: United Nations University Press, 2002.

Below is a list of sites that link you to the UN’s work on Conflict Diamonds:

http://www.un.org/peace/africa/Diamond.html

http://www.globalwitness.org/pages/en/the_united_nations_and_conflict_diamonds.html

http://www.globalpolicy.org/security/issues/diamond/unindex.htm

Monday, October 6, 2008

The Media's Role in putting Conflict Diamonds on the Global Agenda

In the case of conflict diamonds, the media was the tool that a group of small NGOs used to propel the issue onto the global agenda. The media was one of the first targets of these NGOs, specifically newspapers. The coalition Fatal Attraction (discussed in the previous blog) sent editors of large newspapers fake diamond rings in jewelers’ boxes with information on how diamonds fueled wars in Africa (Grant and Taylor). Through my research, this campaign seems to have been effective in attracting the media’s attention- specifically the major Western newspapers.

It is first important to note how I conducted my research. By using the search engine LexisNexis, I was able to track the chronological order in which larger news sources began reporting on the issue of conflict diamonds. By using LexisNexis, I decided to focus my attention on the medium of newspapers and journals. I performed a search on “conflict diamonds” in the past 15 years. The results of my search seem to prove a relationship between the actions of Fatal Action and the issue adoption of major news sources.

Global Witness released their first report on the issue, “A Rough Trade: The Role of Companies and Governments in the Angolan Conflict,” in 1998. In October of 1999, Fatal Transaction began its campaign. (Grant and Taylor). Between the release of the initial report and the start of the Campaign, only a handful of articles were written about the issue. The majority of these articles were written for Africa News, and some of them were written by Global Witness. In The New York Times on August 8, 1999 a short editorial was published: “The Business of War in Africa,” but it wasn’t until October of 1999 that I observed a proliferation of major newspapers reporting on this issue; such as The Times (London), Sydney Morning Herald, The Washington Post, Newsweek, The Economist and the UN began issuing reports to Africa News. I think the proliferation of attention this issue received from the media can be attributed to Fatal Attraction’s campaign, and not as just a mere coincidence.

After the issue grabbed the media’s attention, the UN signed the resolution on conflict diamonds on December 1, 2000. My research showed that between October 1999 and December 2000, 167 articles had been written about conflict diamonds. I think it is safe to state that the UN passed the resolution in part due to the pressure the global media.

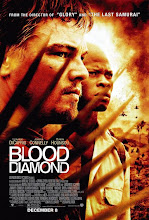

The major newspapers and journals have continued to follow the issue through the establishment of the Kimberely Process, and the release of the movie Blood Diamond. Below is the number of hits my search received from the major news sources on the issue of “conflict diamonds” in the past 15 years:

The New York Times: 27

The Times (London): 36

The Washington Post: 19

Newsweek: 5

The Economist: 3

Overall for Magazines, Journals, and Newspapers: 568

The work of Fatal Attraction and other NGOs properly attracted the attention of the written media. Without the attention and cooperation of these major media outlets, the issue of conflict diamonds may have never made it to the global agenda.

References:

Grant, Andrew, and Ian Taylor. "Global Governance and Conflict Diamonds: The Kimberley Process and the Quest for Clean Gems." The Round Table 93 (2004): 385-401.

It is first important to note how I conducted my research. By using the search engine LexisNexis, I was able to track the chronological order in which larger news sources began reporting on the issue of conflict diamonds. By using LexisNexis, I decided to focus my attention on the medium of newspapers and journals. I performed a search on “conflict diamonds” in the past 15 years. The results of my search seem to prove a relationship between the actions of Fatal Action and the issue adoption of major news sources.

Global Witness released their first report on the issue, “A Rough Trade: The Role of Companies and Governments in the Angolan Conflict,” in 1998. In October of 1999, Fatal Transaction began its campaign. (Grant and Taylor). Between the release of the initial report and the start of the Campaign, only a handful of articles were written about the issue. The majority of these articles were written for Africa News, and some of them were written by Global Witness. In The New York Times on August 8, 1999 a short editorial was published: “The Business of War in Africa,” but it wasn’t until October of 1999 that I observed a proliferation of major newspapers reporting on this issue; such as The Times (London), Sydney Morning Herald, The Washington Post, Newsweek, The Economist and the UN began issuing reports to Africa News. I think the proliferation of attention this issue received from the media can be attributed to Fatal Attraction’s campaign, and not as just a mere coincidence.

After the issue grabbed the media’s attention, the UN signed the resolution on conflict diamonds on December 1, 2000. My research showed that between October 1999 and December 2000, 167 articles had been written about conflict diamonds. I think it is safe to state that the UN passed the resolution in part due to the pressure the global media.

The major newspapers and journals have continued to follow the issue through the establishment of the Kimberely Process, and the release of the movie Blood Diamond. Below is the number of hits my search received from the major news sources on the issue of “conflict diamonds” in the past 15 years:

The New York Times: 27

The Times (London): 36

The Washington Post: 19

Newsweek: 5

The Economist: 3

Overall for Magazines, Journals, and Newspapers: 568

The work of Fatal Attraction and other NGOs properly attracted the attention of the written media. Without the attention and cooperation of these major media outlets, the issue of conflict diamonds may have never made it to the global agenda.

References:

Grant, Andrew, and Ian Taylor. "Global Governance and Conflict Diamonds: The Kimberley Process and the Quest for Clean Gems." The Round Table 93 (2004): 385-401.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)